Introduction

We live in a world which is becoming more and more complex every day. While globalization made challenges more intertwined with the systems that connect us all, internet and information overload led companies and organizations in an unprecedented battle for attention. At the same time, new technologies are creating new opportunities that are causing massive disruptions in society, affecting the way we live, the way we work and do business. Using H. Ritell’s terminology, we are facing a new wave of “wicked” problems — “class of social system problems which are ill-formulated” (Rittel, 1973) — so new solutions and new methods are needed, as the ones previously used to solve many of the problems we face are no longer effective. Einstein captured it greatly when he said: “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them”(Einstein, cited in IDF, n.d.).

The creative problem-solving approach of Design Thinking attracts more and more companies who see in it the means to help them break out of the old molds they have become stuck in, to create alternative ways of looking at a problem. Jon Kolko, in his Harvard Business Review paper, describes Design Thinking as a tool “allowing non-linear thoughts when tackling non-linear problems” (Kolko, 2015). Tim Brown, CEO of the famous design firm IDEO, is recognized for having largely contributed to popularizing “the use of the term Design Thinking to refer to a specific set of procedures, techniques, and methods used to unlock innovation” (Brown, cited in IDF, n.d). However, there seems to be a misunderstanding about what Design Thinking truly is.

This paper explores the many definitions and variations of the Design Thinking process and the role of culture within its application. It outlines the possible barriers that can prevent a successful implementation. The first part is a critical review of Design Thinking and an examination of the culture as an enabler to unleash the full potential of its practice. The second part is a reflection on the practical implementation of the Design Thinking process in the context of a social innovation challenge. It encompasses the evaluation of the specific tools used to solve the brief “Businesses Tackling Homelessness” and the inherent ethical issues.

1. What is Design Thinking?

Although there is a lot of buzz around it, Design Thinking isn’t new. Over the years, the term Design Thinking has been described in lots of different ways giving it multiple meanings depending on the contexts. In her paper “Perspectives on Design Thinking for Social Innovation”, C. Docherty stated that “Design Thinking can be considered a process as well as a mindset, and is widely viewed as [a holistic and creative approach] for addressing ‘wicked problems’ [where multiple spheres and fields collide] and exploring better future” (Docherty, 2017). According to T. Brown and the IDEO methodology, Design Thinking brings together what is desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable (Brown, 2009, p.3); and great innovative ideas happen at the intersection of the three (IDEO U, n.d.), or what T. and D. Kelley, call the “sweet spot of feasibility, viability and desirability”(Kelley, 2014, p.19).

Figure 1. Design Thinking by Tim Brown from IDEO.com

1.1. The Design Thinking process

Albeit the first origins of Design Thinking can be debated, it’s in 1969 that Nobel Prize laureate Herbert Simon outlined one of the first format models of the Design Thinking process which consists of seven major stages. Since then, many variants have been developed, encompassing 3 to 7 stages, though the core of the Design Thinking process leans on the same and most simple model “make, use, learn”, which is also the oldest version invented back to the Neanderthal era.

One of the most popular models is proposed by the Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design, widely known as d.school, the leading university when it comes to teaching Design Thinking. The d.school five stages are: Empathise, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test. During the ‘Empathize’ phase, design thinkers start by doing field and desk research to gain an empathic understanding of the problem they are trying to solve. The second stage ‘Define’ is an analysis and synthesis of all the observations gathered in the previous stage in order to define or reframe the core problem. Then, ‘Ideate’ is about generating lots of ideas through brainstorming activities to spark innovation and selecting the best ones. The fourth stage ‘Prototype’ is about giving life to the ideas previously selected by making inexpensive and scaled down versions of the idea in order to investigate further more the solution. Finally, the fifth stage ‘Test’ is about evaluating thoroughly the solution ideally with the people we have designed it for, in order to collect feedback that will help to refine the solution (d.school, 2009).

Figure 2. d.School Design Thinking

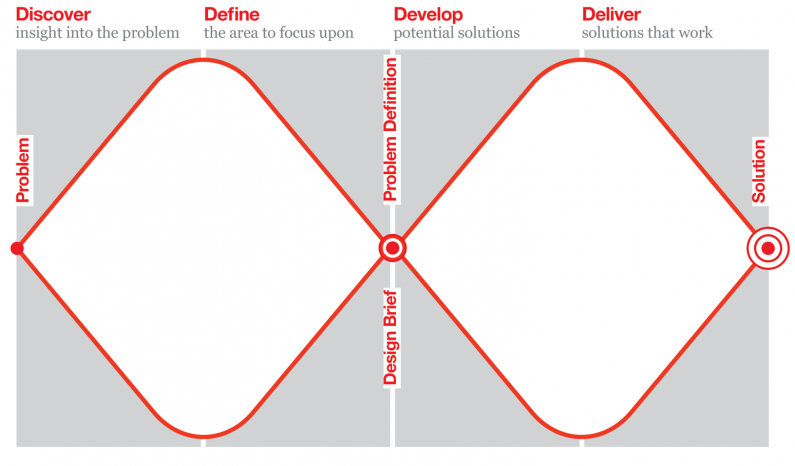

In 2004, the Design Council created the “Double Diamond” model in an attempt to combine the different approaches and ways of working of every design discipline in a simple visual map. Although the number of phases is four, the process is quite similar to the d.school one. In my opinion, the Double Diamond shape brings a better clarity to what each phase is about. The Design Council explained that “In all creative processes a number of possible ideas are created (‘divergent thinking’) before refining and narrowing down to the best idea (‘convergent thinking’), and this can be represented by a diamond shape. But the Double Diamond indicates that this happens twice — once to confirm the problem definition and once to create the solution” (Design Council, n.d.). In T. Brown’s words, ‘divergent thinking’ is about “creating choices”, while ‘convergent thinking’ means “making choices” (Brown, 2009, p.67). Though the diamond shape brings some clarity about the kind of thinking used at each phase of the design process, J. Ball, one of the people involved in creating the model, argued during a talk at Hyper Island on 6 October 2018, that the perfect symmetry is just a graphic convenience that doesn’t reflect other parameters such as time or scope (Ball, 2018).

Figure 3. Design Council Double Diamond

The Interaction Design Foundation explains that despite the apparent order and logic in the way that one stage leads to the next one until the completion of the solution, all these models share the same iterative and non-linear nature of their processes. This core aspect of Design Thinking seems to be often misunderstood by businesses who understand it as a step-by-step process, though the different phases should be understood as different modes that contribute to a project rather than sequential steps. This wrong interpretation of the Design Thinking process might put the whole discipline at risk as companies would lose the learning potential of the method that continually collects and uses the information to both inform the understanding of the problem and solution spaces, and to redefine the problem(s). Besides, all variants of the Design Thinking process embody the same principles first described by H. Simon (IDF, n.d).

1.2. The Design Thinking mindset

In “The Sciences of the Artificial”, H. Simon first introduced design not so much as a physical process but as a way of thinking (Simon, cited in IDF, n.d.). Later, T. Brown took over this idea when he explained that Design Thinking is firmly based on generating a holistic and empathic understanding of the problems that people face, and that involves ambiguous or inherently subjective concepts such as emotions, needs, motivations, and drivers of behaviors. This contrasts drastically with a scientific approach that relies on quantitative research to understand the user’s needs. T. Brown captured this idea in introducing Design Thinking as a third way: “Nobody wants to run a business based on feeling, intuition & inspiration, but an overreliance on the rational and the analytical can be just as dangerous. The integrated approach at the core of the design process suggests a third way”(Brown, 2009, p.4). In short, Design Thinking combines two very different ways of thinking: analytical thinking and creative thinking; a marriage between logic and imagination, that together can spark new possibilities. Einstein summed it up when he stated: “Logic will take you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere”(Einstein, 1996, p.481).

The design way of thinking leans on a set of principles, as previously mentioned, that guides the ethics of the Design Thinking process. According to d.school, the first principle demands that the design thinker question everything: the problem, the assumptions, and implications in order to get to the root causes of the initial problem. Another main principle is about placing the people designers are designing for at the center of the design process. This links to empathy as a foundation of Design Thinking. The third principle is about communicating visually: visualizing information, in order to make our personal mental models or representations of the external reality, visible to the outside world, and by that, to the team. Then, the forth core principle is about collaboration and co-creation. Design Thinking is collaborative and inclusive as it aims to include stakeholders in the design process but also to build teams with people from varied backgrounds and viewpoints in order to enable breakthrough insights and solutions. Finally, another important principle is the iteration, as previously mentioned. The idea behind is to release solutions quickly in order to gather continuous feedback. These principles are just the main ones among other rules. They all contribute to providing guidelines in the application of the process such as creating a more democratic approach to decision-making, or a more experimental approach to the innovative process (d.school, n.d.).

2. The practice of Design Thinking in social innovation

The second part of this paper is a critical evaluation of the application of the Design Thinking method and tools applied by a multi-disciplinary team in response to a client brief in the context of a social innovation challenge. The Double Diamond model will be reviewed thoroughly in each of its four stages, as it was the method chosen by the team, with a focus on the application of the Design Thinking principles along the journey. The process will conveniently be presented in a linear fashion through the reality was more scattered and overlapping. The brief given to the team was created by the agency Noisy Cricket in collaboration with the Manchester Homelessness Partnership: How can we improve the system, cultural and personal process to enable those people looking for gainful employment to find their success story? Given the wide scope of the brief, the client pointed out that the main focus should be on how can we remove or reduce the barriers for businesses to hire those people. Considering the level of complexity that represents the homelessness issue, the challenge can be considered as a perfect example of a wicked problem.

2.1 Setting the team culture

Beforehand, the team began this collaborative journey by creating a “Team Canvas”, a strategic framework aiming to help team members align on a shared vision, including goals, values, roles, and rules. Setting the canvas was a meaningful starter activity that enabled team members to learn about each other, though the usefulness of this activity has dropped down very fast the next days as team members didn’t remember the content when the related discussion arose. It seems that a physical “living” tool placed in evidence in the workplace environment, that can continuously be discussed and adjusted if necessary, could better support the team through the whole project.

Photo 1. Team Canvas

2.2 Phase 1: Discover

During the discovery phase, primary and secondary research allowed the team to gain an empathic understanding of the problem and the people involved in it, who are they, what are their needs and the barriers they face. Desk research was used to identify existing organizations already fighting the issue while interviews with an ex-homeless person and professionals in homelessness employment initiatives, from both the business and charity sides, helped question assumptions and uncover underlying issues. However, it was not until an interview with businesses willing to get involved and an immersive field trip at a homeless day care center that a deeper personal understanding of the issues involved emerged.

The ‘discover’ phase built the foundation for the whole project as it helped the team to empathize with each stakeholder and gain valuable insights at a systematic, cultural and personal level. Though questioning everything gave the team the deeper understanding needed to pursue the process, the practice raised some ethical dilemmas such as misrepresentation and reservations about the businesses’ motives. Besides, given the scope and limited time of the project, this stage was daunting for the team at times regarding the difficulty to evaluate if enough information had been collected in order to make an informed decision in the next stages. It is important to note that the team continued to pursue the research during the whole duration of the project, which was a crucial element in the decision-making process.

2.3 Phase 2: Define

In order to organize, interpret and make sense of all the data gathered, the team used a tool called “Download your Learnings” which allowed team members to transfer their own findings into post-its and share them orally with the group before clustering them on the wall. Other tools such as “empathy map”, “personas” and “stakeholder map” were applied, which contributed to connect the dots and develop new and deeper insights. For instance, businesses who would like to do good just do not know where to start; and only a part of people with lived experience of homelessness is work ready (“Alex” is the term that will be used for the rest of the paper when referring to them). The lack of jobs and the need for appropriate support for new hires for both businesses and Alex were also insightful information. From the analysis, the definition of a problem statement was formulated and flipped into a human-centered, meaningful, and actionable question, aiming to bring clarity and focus to the design space: How might we use the existing knowledge and successful employment programmes to make it easy and attractive for businesses to hire Alex?

Photo 2. Research board

Photo 3. Stakeholders Map

Setting a physical research board giving everyone the same level of knowledge, was highly beneficial for the team, as the first step of the ‘Define’ stage. However, it is important to note that quality in visual communication is essential to enable information to be easily reviewed at a later stage. Albeit applying a human-centred approach to a social problem seems particularly appropriate for the nature of the brief, putting the user at the center of the design process was challenging, as four main stakeholder groups had to be considered as “users”, making the approach itself confusing, especially when applying tools like the stakeholder map, as it rose the question of who should be in the center. Besides, even though Design Thinking is not a linear process, I would argue that inside the ‘Define’ stage, some tools need to be used in a specific order to yield a meaningful outcome at the end.

2.4 Phase 3: Develop

When starting ideation, the group took time to find the brainstorming activities that can generate the more ideas possible while trying to suit each other working styles. The team chose to articulate the session in two steps. First, the “Negative Brainstorming” and a hacked version of “Crazy 8”, were used as ice-breaking exercises that enable participants to lose their inhibitions and stimulate free thinking in order to generate more unusual ideas. Secondly, a bespoke “Silent Brainstorming”, where participants build on the pool of ideas generated previously, prevented further potential ego problems when deciding on a solution. From there, the team was able to converge on one main idea including the best part of other ideas, using storyboarding as a medium. The chosen concept was a festival for Alex by Alex uniting the public, Alex, businesses, and charities — all in one place.

Photo 5. Hacked Crazy 8

Photo 6. Storyboard

The ‘Develop’ stage is the peak moment of the process when extraordinary unorthodox design solutions can happen if the culture in place allows it. However, the inclusive nature of Design Thinking of bringing people from different background together is more challenged during this stage of the process, as sketching can make non-designer uncomfortable with the activity even if trying to create a safe space. Moreover, certain tools work for some people but rarely for everybody on the team. On the other hand, the application of democratic principles such as giving an equal voice to each team member when sharing their ideas plays a crucial role in the process. Therefore, to balance the high expectations of this stage and the pressure on team members to be creative at this particular moment, tools and rules need to be carefully chosen to yield satisfying results without compromising the team cohesion. Furthermore, a participatory approach, as bringing stakeholders into the ideation process, could have benefited the solution’s accuracy and later adoption, while removing some of the pressure on the team.

2.5 Phase 4: Deliver

To communicate our idea within the team and later on to the clients for the pitch, the team developed a series of rapid prototypes. The first attempt was to create an opportunity card using the “why, what, how” approach to clarify the vision. It turned out that team members had very different interpretations of the concept because of the broadness of activities and goals behind them. It was not until mapping out the idea of a “customer journey” that a common understanding of what the festival was about and how it could take place emerged. After agreed on the concept’s key features, some ethical debates arose: could it harm some Alex more than helping them if they don’t get a job after the festival? Is it worth it if we help 70%? 50%? 30% of them? Are we more helping companies to show they are doing good?

The ‘Deliver’ stage is the more experimental part of the process when ideas come to life in order to be shown to users, though it is not until the pitch day that the team could collect feedbacks. Prototyping played an essential role in helping the team visualize the solution, and get a more informed perspective of the constraints and how real users would behave, think, and feel when interacting with it. However, some ideas such as a festival might be difficult, if not impossible, to prototype and test. This joins Rittel’s definition of a “wicked” problem as “there is no immediate test of a solution to a wicked problem and, every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation”; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly” (Rittel, 1973). Therefore, Design Thinking and wicked problems seem to be at odds with each other as one core principle of the discipline is about testing the idea with real users and learning from it. This suggests that the Design Thinking method need to be tweaked when solving the wicked problem. But is it ethical to do so in the context of social innovation?

Photo 7. Customer Journey of the concept

Conclusion

The two parts of this paper discuss the value of Design Thinking in solving wicked problems, the importance of culture and the ethical issues related to its practice in a social innovation context. From research and analysis of relevant academic and professional literature, as well as the personal experience of applying the method, it can be concluded that Design Thinking can unlock the creative and innovative potential of multi-disciplinary teams if its individuals also embrace the inherent mindset behind the process to support a collaborative culture and democratic approach to decision-making. Albeit Design Thinking is a good tool for simplifying and making human sense of things when solving wicked problems in social innovation, the inherent ethical dilemmas of its practice need to be carefully addressed in order to drive the “right” kind of change.