Partnering with startups represent a shift in how designers think, feel and operate throughout the design process. Are your collaboration muscles flexible enough for that change?

Over the last few years, R/GA Ventures has partnered with more than 80 early- and growth-stage startups from different verticals and industries. From defining their go-to-market strategy, to creating brand and design systems, to redesigning product experiences — we have been using our creative capital (our talent) to help accelerate and augment the reach of startups that are already disrupting their field.

We are talking about a wide range of products and services here.

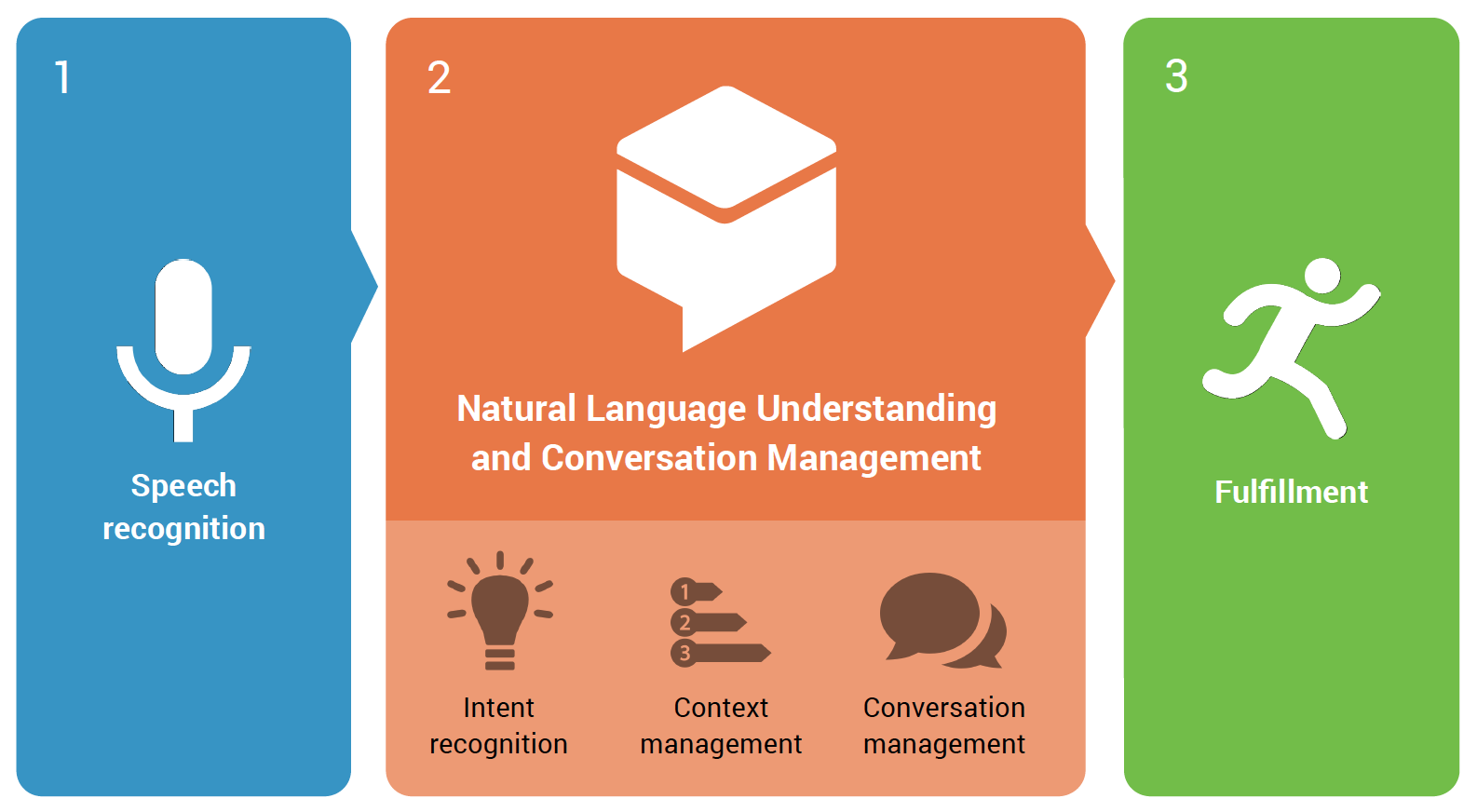

Connected devices, artificial intelligence technology, logistics, analytics tools, retail systems, wearables, chatbots, physical installations, sensors, educational platforms, CRM tools, and more.

Personally, as a designer who has always worked with huge brands (Google is one of our main clients at R/GA San Francisco), moving into these Ventures programs represented a big shift in terms of how I think, feel and operate throughout the design process.

What are the differences when it comes to collaboration, design process and solutions?

The product is often still being defined

For some of the startups working with R/GA in our Ventures programs, the product is still at its early stages of concepting and testing. It’s not uncommon to find startups that have focused their efforts in developing a powerful technology, but haven’t fully defined their product’s value proposition and how its functionalities map to their users’ needs.

In early interviews with the startup founders, we often times hear that “all we need is a few usability improvements to our existing interface” — but as they start to collaborate with R/GA’s strategists and designers, they realize the different parts of their ecosystem is more connected than they thought. A simple change in one of the pieces will have a huge impact in other parts of the system. So the best solution might be to step back and think about the user experience more holistically, as a broader ecosystem, and instead of usability fixes, come up with a new design system that will avoid usability problems from happening in the first place.

UX improvements have higher value

We are working with new products that are still trying to expand their user base and reach new audiences.

For that reason, the onboarding experience plays a really important role in the overall success of the company. It’s the moment of truth: the initial steps of the interaction between users and product that will make them decide whether that will be a relationship of love or hate.

As a designer, it is important to help the startups understand the impact design can have in those initial moments. The more traction the company gets, the more people will be accessing the website, signing up for the service, downloading the app and spreading the word about the service. Even the smallest improvements to the user experience can have a huge impact on conversion rates and satisfaction scores.

You have to be ready for change

These companies are usually trying to disrupt a certain market, which also means a lot more uncertainty when it comes to the company’s position in the market and how the fluctuations happening externally might affect the company.

For designers, working with startups means the design process has to be flexible enough to quickly adapt to change. It’s not uncommon to see foundational changes in the product direction halfway through the engagement with the startup.

Be ready for change. Knowing how to work with an agile mindset, having alternative versions of the product ready to implement, and learning to think beyond the current product functionalities are some of the good practices for designers who are looking to add value to the startups.

You’ll be white-boarding with the CEO

When you are working with startups, you have much more access to the company’s founders and partners on a daily basis. A quick walk around one of our Ventures Studios will let you see R/GA’s designers white-boarding UI ideas with the startup CEOs in a room.

Don’t be alarmed if these CEOs don’t match your expectations of what a CEO looks like; these are hands-on entrepreneurs that are trying to disrupt an industry, make a change, and who have been trained in a much more collaborative mindset than more traditional founders and leaders.

All this access to the C-suite is extremely powerful for the partnership between agency and startup. It speeds up the decision-making process and enables ideas to go from paper to product in a matter of weeks.

No bureaucracy. Everyone wins.

Ideas have to be validated as quickly as possible

As in any other client engagement, the role of Experience Designers in the process is to represent the user’s voice as the team makes design decisions about how the product is going to function, behave or look.

When working with startups, user research is more important than ever — exactly for the other reasons aforementioned. But we often take a more nimble and recurrent approach to user research, instead of treating it as a project in itself; every decision goes through some sort of validation, whether that means in-house user-testing sessions or a quick focus group exercise. Startups in earlier stages usually have great relationships with their beta users, which makes it fairly simple to get on the phone and invite some of those users over for a quick conversation.

Brand and product are being shaped together

When working with big companies, our role as designers is to understand the organization’s values and beliefs and to translate them into product interface moments that will shape one’s experience with that brand.

In a lot of startups, the brand is being defined at the same time as the product — and often times these two things mix up more than one would expect. Design works hand-in-hand with branding, and the process becomes much more bi-directional and collaborative: product definitions help shape the brand, and brand definitions influence product decisions.